In Windsor, everyone you talk to has a view of who should run a property that dominates the city’s economy –and skyline – by providing more than 2,000 jobs and anchoring the tourism industry.

The Ontario Lottery and Gaming Corp., the provincial agency that owns the property, is in the final stage of reviewing offers for what’s historically been a licence to print money.

While the process is meant to be secret, three gambling industry sources say there’s a three-horse race for a property that draws millions of tourists to the border city. The company that has run the casino for three decades – Las Vegas-based gambling powerhouse Caesars Entertainment Inc. CZR-Q – faces the prospect of being usurped either by upstart Bally’s Corp. BALY-N, which was built from casinos and a brand that Caesars sold, or Indigenous-owned Mohegan Gaming and Entertainment, which operates two casinos in Niagara Falls, Ont.

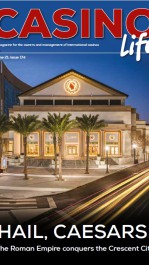

Image: Caesars Windsor Casino Windsor Ontario - Picture credit Shutterstock

The Globe and Mail is not identifying these sources because the OLG prohibits them from publicly speaking on the selection process. Spokespersons for the OLG, Caesars, Bally’s and Mohegan declined to comment. The OLG is expected to announce the new licence holder by this fall. If the agency picks a new operator, it would take over in 2025.

Among city leaders – the mayor, tourism executives and union officials – support for Caesars is universal. If the OLG awards the licence to another operator, it will be yet one more controversial decision from an agency that has already faced pointed criticism from the provincial auditor-general over the way it picks partners.

“Caesars should be the favoured candidate, based on the job they’ve done running the casino and providing quality jobs,” said Dave Cassidy, president of Unifor Local 444, which represents workers at the facility. He said Windsor Mayor Drew Dilkens also backs Caesars’ bid to remain the operator.

In the face of growing competition from online gambling and new casinos, Mr. Cassidy said Caesars has consistently invested in the business to build its client base. In the wake of Windsor’s success, three casinos opened in neighbouring Detroit. And the OLG has licensed 30 properties since 1994.

“Windsor needs an international casino operator who can do what’s needed to win customers and stop them from playing across the river in Detroit,” said Mr. Cassidy. He estimated it would cost a rival operator at least $80-million to rebrand the property if Caesars loses the licence.

“It’s critically important that whoever OLG chooses to run the casino have an established brand, with the gambling expertise and the loyalty programs that keep patrons coming back,” said Gordon Orr, chief executive officer at Tourism Windsor Essex Pelee Island.

Globally, Caesars has built a customer loyalty program with an industry-leading 60 million members. In Windsor, these customers get VIP treatment that starts with their own entrance to a reserved parking lot. In an interview at his office, a block from the casino, Mr. Orr said: “We’re playing in the big leagues here, competing against sophisticated casino operators.”

In 1994, Ontario’s then-NDP government licensed the province’s first casino as part of a union-backed plan to revitalize the downtown of a struggling border city. On opening day, gamblers lined up around the block to get in. At the time, Mr. Orr managed a Best Western hotel just down the street, a property scrambling to attract guests. Caesars solved the occupancy issues by reserving entire floors, year-round, for its high rollers.

“The casino was the tide that lifted all boats,” said Mr. Orr. In 2022, the Windsor region welcomed 4.4 million visitors, who injected $669-million into the local economy. “For the tourism sector, Caesars put us on the path to prosperity,” he said. “In the hospitality industry, the casino offers destination jobs.”

Over three decades, the casino moved around Windsor’s downtown, from temporary space in the art gallery to a riverboat to its current home in a redeveloped convention center, built at a cost of $1-billion.

“Back in the day, Windsor had its identity as an automobile city tattooed on both arms,” said Chris Vander Doelen, a former Windsor Star journalist and politician who co-wrote a book on gambling in Canada. “The casino successfully changed the city’s view of itself.”

On Caesars’ watch, the property weathered one of North America’s first smoking bans, which cut traffic temporarily; the introduction of passports for cross-border travel; and COVID-19 pandemic restrictions. Today, a stroll through a casino the size of two football fields reveals a masterpiece of insight into human behaviour.

It is all but impossible to move between the 760 rooms in two hotel towers, the six restaurants, a nightclub and concert venue that’s hosted Billy Joel and Diana Ross without stopping at a flashing one-armed bandit, excited crowds around a craps game or a kiosk that takes sports wagers. After enjoying a bottomless coffee at the Johnny Rockets restaurant adjacent to the gambling, I headed for a washroom, only to find myself slowing down to bet $10 on the Pittsburgh Steelers to win the Super Bowl.

Caesars is also viewed as a leader in meeting the traditional casino’s most significant business challenge: online gambling.

“Caesars has created an exciting digital experience that’s seamlessly integrated with their casino experience,” said Paul Burns, chief executive officer of the Canadian Gaming Association. ”They’ve been purposeful in giving people a reason to come to Windsor, and built a customer base that reaches from Chicago to Pennsylvania and across Ontario,” he said.

NASDAQ-exchange-listed Caesars is a favourite stock pick for analysts like Brandt Montour at Barclays. In a recent report, Mr. Montour said he was “bullish” on the company’s prospects because of its strategy of blending the gambling experience at flagship properties in Las Vegas with regional casinos, including Windsor, and its digital-platform promises to retain existing customers, while drawing a new generation of gamblers.

On a weekday visit, retirement-age gamblers half-filled the floor at Caesars Windsor, with many arriving in tour buses. Mr. Orr said on weekends, the casino draws a younger crowd, including bachelorette parties and 20-somethings looking for a place to start their nights.

Caesars is one of the world’s largest gambling companies, with 53 casinos, including 15 properties in Nevada. Providence, R.I.-based Bally’s operates 15 casinos. Uncasville, Conn.-based Mohegan runs eight casinos.

Gamblers in Windsor make a significant contribution to both Caesars’ bottom line and government coffers. While the company and the province don’t disclose specific financial results for the property, their overall numbers show the casino is a major money-maker.

Caesars owns or leases the majority of its 53 casinos. The company manages just seven properties, including the Windsor casino. The company’s financial results show this small division is Caesars’ most profitable line of business.

The seven managed casinos earned US$83-million in the first nine months of 2023, up 30 per cent from the same period in 2022, with a 34-per-cent profit margin. (The company reports year-end results next month.) Caesars’ overall revenues – for all gambling – were up 9 per cent to US$8.7-billion in the same period.

For Ontario’s deficit-running government, gambling is a major source of revenue. Last year, the OLG took in $4.2-billion from its 30 casinos. The cash was evenly split, with $2.1-billion going to provincial coffers and $2.1-billion paid out to Caesars and the other companies that run the properties. To put that figure in perspective, Ontario received $2.29-billion from the government-owned liquor retailer, the LCBO.

The OLG pays a portion of its casino revenues directly to the city of Windsor, handing over a total of $88-million over the past three decades. The quarterly payments amount to 2.5 per cent of the city’s annual budget.

Caesars’ long run in Windsor came into question last April, when the OLG put the contract out to tender. The move marked the final stage in a dramatic shift in the way the province licenses casinos, a policy change that has been playing out for more than a decade. Caesars Windsor is the last contract to be redone.

The OLG’s goal with the new licences is to increase the province’s take, while encouraging operators to invest in facilities. In the past, the agency and casino companies simply spilt gambling revenues. Now, operators must guarantee a pre-determined annual payment to the OLG. The companies get to keep 70 per cent of revenues above this amount.

Controversy dogs the transition. In 2022, the provincial auditor-general published a report that criticized the OLG for allowing three casino operators to redo their 20-year contracts after pandemic restrictions were lifted, and reduce their guaranteed payments.

The auditor-general also faulted the OLG for handing out licences without balancing guaranteed payments against the operators’ commitment to invest in their casinos. Provincial accountants zeroed in on the OLG’s decision to award the two Niagara Falls casinos to Mohegan in 2018, despite Caesars pledging $140-million more than Mohegan to spruce up the properties in its unsuccessful bid.

In response to the auditor-general’s review, the OLG pledged to hold operators to their payment guarantees and put an increased emphasis on investment in casinos when renewing licences.

Last October, the OLG finished its initial review of bids for the Windsor casino and started negotiations with potential operators. The process is meant to be confidential. Caesars and the companies vying to replace it aren’t supposed to know who else is in the race.

However, to minimize disruption for guests, the OLG scheduled site visits for the outside bidders on the same day last fall. Casino executives spotted rivals in Windsor. And the gambling community is small. In Windsor, it’s an open secret that Caesars is the front-runner, and Bally’s and Mohegan are also in the race.

The company that ends up running Ontario’s oldest casino faces the challenge of both keeping the property competitive and continuing to rejuvenate Windsor’s downtown. City leaders have strong views on both issues.

Caesars closed a massive buffet-style dining room during the height of the pandemic, for health reasons. The space hasn’t reopened. Unifor’s Mr. Cassidy says while the buffet is a money-loser for Caesars, bringing it back would be a hit with guests. He is also pushing Caesars to expand a relatively modest sports-betting facility into a space with more screens, more bars and more employees.

Windsor also cries out for more development in the vacant blocks surrounding the casino complex. Mr. Vander Doelen said the casino has been a “black hole” since the day it opened, with gamblers spending all their money in the casino and making no contribution to other downtown businesses.

“The problem with a destination resort like Caesars is visitors have no reason to leave the building,” said Mr. Cassidy. “The city needs businesses to build the malls, the restaurants, the condos and maybe an arena that attract even larger crowds.”

These are the challenges facing whichever big-league operator wins the right to oversee the next two decades of Windsor’s lucrative relationship with its casino.

Source: The Globe and Mail

Preview Image: Caesars Windsor Casino Windsor Ontario picture credit Shutterstock